accepting poetry, short fiction, vignettes, memoir fragments, essays, opinions, reviews, and whatever else of interest

Please send work in a word file to koonwoon@gmail.com

The Committee promises that the best on the site will be in a paper volume

send work in a Word file to koonwoon@gmail.com

Poetry

Diner

by Liam Roche

The sun holds back no brilliance, and the day is cold despite this.

The boy waits for the girl while he sits at the center of the diner filling with morning.

The waiting is ancillary.

Among the few there murmuring, he hears other murmurings which rise and fall, searching for opportunities to harmonize.

And clouds do pass too and fill the room and the street and the city with the tension of shadows in a slow-motion siren of light.

It is on this stage the coffee steam rises and creeps, the silverware clatters, and the Formica sparkles with its own stars in a frozen green universe.

He is gone into it.

The girl, a few blocks away, wonders if this boy could be trained to be something else—to lose his strangeness, to be like other boys, to have his handsomeness made thorough.

She is imagining embracing him in ways that wake him from his dreams.

At first, the boy is not thinking of her. He is losing himself in another moment in which everything speaks.

And then he also sees the two of them embracing while the checkered tile floor and the green countertop and everything in the universe vibrates as voices of angels, and all light is overcome,

and he holds her tight not out of simple love, but to keep God from falling out of her.

LFR 2018

Liam Roche survived and enjoyed a large Irish Catholic family in New Your City with parents who followed its beatnik vibe from the early 1960’s onward. Both parents were artists and actors of good success. (Eugene Roche.)

As a child, he was surrounded by pre-famous yet unemployed artists, musicians, actors, all manner of specialists in the arts of wonder, looking for the next gig. His household was full of song, loss, drama and love.

Today, Liam writes on topics that fuse spirituality, profanity, absurdity and delicate love.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Tao Qian

Drinking Wine

Tao Qian

| Settle home in person place But no cart horse noise Ask gentleman how able so Heart far place self partial Pluck chrysanthemum east hedge down Leisurely look south mountain Mountain air day night beautiful Fly birds together return This here have clear meaning Wish argue already neglect speech | I made my home amidst this human bustle, Yet I hear no clamour from the carts and horses. My friend, you ask me how this can be so? A distant heart will tend towards like places. From the eastern hedge, I pluck chrysanthemum flowers, And idly look towards the southern hills. The mountain air is beautiful day and night, The birds fly back to roost with one another. I know that this must have some deeper meaning, I try to explain, but cannot find the words. |

View Chinese text in traditional characters.

Other Chinese poems about Separation.

Memoir Fragments

MEMOIR FRAGMENT

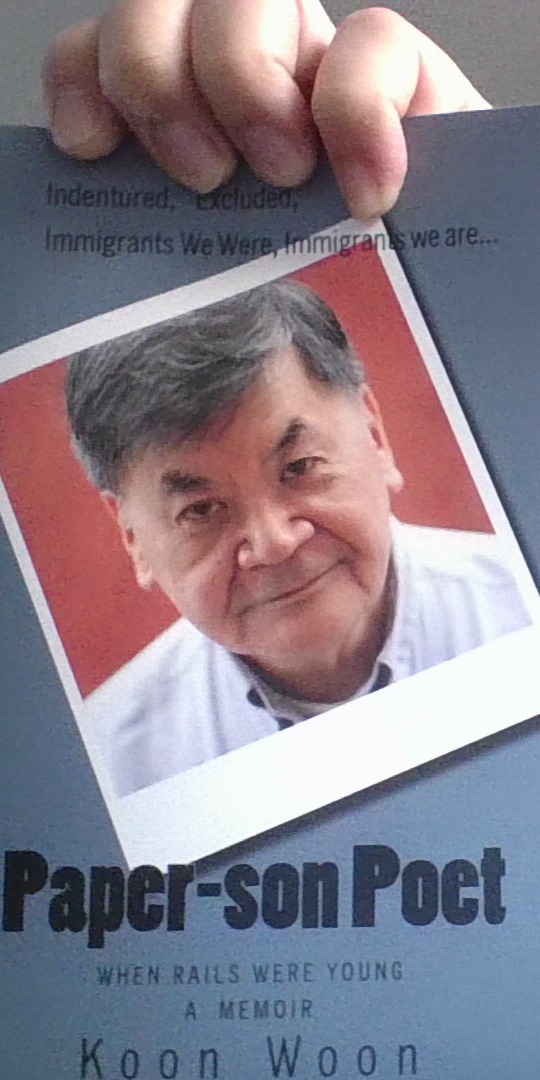

Mon Ami [Koon Woon, BOF 4/2/24]:

Mon Ami, in high school, I smoked just a few puffs of grass, a good student, and had the usual amount of acne. But I was lonely beyond constipation. I sat in comatose coffeeshops instead of going to games or dances, didn’t even drink illegally. Didn’t date at all because my parents were reversed racists. They talked of family all the time how the whites weren’t like us the Chinese. “They got no family,” my dad’s favorite pronouncement. “They are like a pack of dogs, when one comes, they all come,

yelping and barking ‘til they got served.”

I had no ambition to go to Paris, or to fall in love, I was still dreaming of my village water-buffalo and the muddy rice paddies. We were peasants there. Here I wear the yellow waiter’s jacket, which has been worn for three generations. Else I am in a white apron in the kitchen, stirring chop suey. Secretly I was reading Freud and a book I picked up at the drugstore called Psychosexual Infantilism. Case histories, you know. You couldn’t find a single book of porn in the entire town of Aberdeen. So, I went to the “alternative bookstore” to buy a copy of the Detroit Free Press, where there were funny ads about AC-DC hookups. Something about prostate massage, and ads for various “toys.” I was browsing the bookrack at the Highway Grocery, an all-night mom and pop grocery and café, and I fingered Portnoy’s Complaint, and George, the owner, beamed with approval and blurted, “Great book. I finally found someone with more problems than me!” But like I said, I was more “clinical,” because I read Freud himself. I read Nietzsche too, because although I doubted the existence of God, here is someone that said God is dead. It freed me from unnecessary doubt.

The Beats were in San Francisco, and I was in the small fishing and logging town of Aberdeen on the Washington coast. We got paper and pulp mills that stank up the whole town and spewed sulfur fumes into your lungs. I heard about the Beats, but I was a few years too young for them, sort of like the “teenyboppers” of the later Hippie era in Seattle I was in. In Aberdeen, I was in the crucible of the chemistry class and the insular womb of the Chinese American family. My parents are first generation, and I was what they called generation 1 and ½ because even though I was born in China, my formative years were written in the US.

My father was Confucian and macho. He smoked Marlboros and went duck hunting with a shotgun. Before he started his own restaurant, he was a fry cook for the mayor’s Smoke Shop Café, he was a bookie to the selfsame man. Making odds for football point spreads. My dad taught my brother Hank too. Hank later joined the Army and became a supply clerk. Even though Hank could write the longest Cobol computer programs, he couldn’t keep track of the army provisions and all kinds of things were missing. At the end of his tour, Hank came back to Aberdeen already a drug addict.

My mom struggled with English. She worked as waitress and cook and housewife. With eight kids, all she needed was four hours of sleep a night. But my mom genuinely loved people and their money, and was after all, culturally subservient as a proper Chinese woman. That is why I laughed so hard when I saw the movie “My

Big Fat Greek Wedding,” where the mother in it said, “Yes, the man is the head, but the woman is the neck, and she can turn him any way she pleases.” I also like the part where the father said to the prospective son-in-law, “We were philosophers when you guys were still swinging on trees.” We Chinese can brag about the abacus, because a group of mathematicians at Cambridge University in England had shown that it was mathematically equivalent to Markov Chains and the Turing Machine. That makes the abacus the first computer in the world. In school, I was known as a “brain,” a quiet one, one that waited on tables for his classmates’ parents and occasionally his teachers’ families. This makes me think of “The Monument of the Unknown Citizen,” a poem by W.H. Auden. I never complained. I battled against myself in the middle of the night, playing a chess game out of the book Chess Made Simple. I also wish that there was a book called Simple Simon Made Simple.

In some sense I was a leaky boat, peddling to the middle of the ocean. I didn’t even know that I myself carried a genetic time bomb. Later when I went up to Seattle to pursue a university education, the freedom made me wild. But in spite of my ambition to be a coffeehouse intellectual, I read serious books in literature and in mathematics and philosophy. My manic spells distorted my view of myself. I thought I could be a guru without meditation, an athlete without workouts, and I actually believed in a “castle in the sky,” when I took my first hit of acid.

[Actually, things started on October 31, 1960, when my plane landed in Sea-Tac Airport. It was Northwest airlines. You know, I was loyal to them for decades until they got subsumed to Delta. Their hub was Minneapolis, Minnesota, where many years later I would navigate the airport on the way to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. That was when my real life began, a story we would eventually get to.

[What is life, the philosopher asks: is it the “appropriate arrangement of matter?” My second life is a literary life. I often mused that all you need to be a writer is a pen and paper, but you don’t even need that once you become famous; you can dictate your words to the secretary. We always forget about the brain /mind. And language, and language assumes a community, a shared history. And that’s why I think the Russian Formalist were not far off. The “text” is floating out there in the communal linguistic pool. Someone is bound to come along and write it.]

Don’t sweat it, Koon. You are never going to be Jacque Derrida. Just do what you can. And you know if you ever meet Derrida on the plane, you better not say “Hi” to him, you will get arrested for attempting to “Hi Jack” the plane. Best to stay anonymous, my friend, and do work quietly. That way you can continue to claim your disability, get student loans to go to school, learn differential equations that link a function and its derivates all into one equation. There is something unforgiving about that, almost like a blood debt to the Mafia.

You will go far into the world before you are recognized in your hometown.

As I was saying, or didn’t say yet, I was born in the hour of the Rooster, the Year of the Rat in 1949 in a small village in southern China near Canton (Guangzhou). Not long after my mother’s teats were withdrawn from me because she immigrated to America with my father. Left to the care of my grandmother and uncles, I was a precious crybaby, and my grandmother never let me out of her sight. Everyone treated me well because someday I was to go to America, the Golden Mountain, as it was known in China. Alternatively, it was known as Mei Kuo, meaning “beautiful country.” But because we used manure for fertilizer in our village rice paddies, we called our land “fragrant.” I mean, of all things, we misnamed everything, not heeding what Confucius said, “The first step to knowledge is calling things by their correct names.”

Sometimes you should just “free write” anything that comes to your head. Because you can revise, edit, and rewrite, and so nothing is wasted. A gem cutter or a sculptor creates art by discarding what’s unnecessary. That reminds me of a story of a jade carver in ancient China.

You see, the Chinese consider jade to be magical and it is the most precious stone to the Chinese, and never mind for the moment that there are nephrite and jadeite. Jade carvers in ancient times were looked to with reverence because they can see the inner soul of a piece of stone. They fast and meditate for days to envision what a hunk of stone contains. The story has it that a rich man had a very large piece of stone, and he greedily wanted it carved into a mansion. But the jade carver told him, rubbish, there is only a bunch of grapes here, not a whole mansion. What is unsaid, of course, it is not only the owner can’t get what he wants, all he gets is sour grapes.

Memoir Fragment

- by Koon Woon

Simonson’s coffee diary

Gene Miller was our coffee man. He brought Simonson’s condiments and coffee. He was the son-in-law of the owner. Proudly talkative of his older daughter who was chief accountant for King County, Gene bragged how no one can figure out his daughter’s bookwork. The transactions must have been like the interconnected tunnels of prairie dogs. Not visible at first glance but there is a subterranean series of tunnels, entrances, and exits that only she knew. And as you know, prairie dogs alert one another through their tonal language. The pitch of a sound mattered in its meaning, like Chinese language. We were a Chinese-American restaurant, and we served coffee because it was American and hot mustard and sesame seeds with sliced barbecue pork; that was Chinese.

Gene had another daughter. The younger one was Marti, and she was my classmate at Aberdeen High School. Gene knew that because Marti talked about me at home no doubt because I was the literary chair of the creative writing club of which she was a devoted member.

Four decades later I went back to the Aberdeen Public Library to give a reading of my poetry, celebrating my second book of poems. Marti came and she did not look well. She was now a self-proclaimed artist. I knew she must have been bipolar, like me. The librarian was upset Marti took so much time talking during the question and answer period following my reading. I told the librarian later that Marti had been my classmate. The librarian then said, “It is truly remarkable you can talk everybody’s language. I told her I had been around and that a poet needs to know a bit of everything. Disenfranchisement seemed normal to me, and so I got “in” with the “out-crowd.” There are some still out there, but a tremor or a facial tick gives them away, even before they become talkative of nothing in particular and then suddenly lapse into a sullen mood because no one cared to listen. Drinking coffee to excess can also make one chatter much. Gene the father never talked about Marti. And so Marti talks a lot to define herself.

Poetry

by John Grey

THE RECEPTION AFTER THE READING

Young women gathered around

the well-known poet.

The lesser-known male poets in attendance

stood in line for wine.

One of his admirers

brought his glass of cheap red to him.

He put it to one side

for he had books to sign.

In a city of Providence’s size,

I estimate there’d probably be

twenty to thirty females

in their twenties

willing to gush and sigh over

some guy who has a way with words,

is under forty

and is passable looking.

At least half of them

were in attendance that night.

The lesser-known poets attract

none of these women

Their poetry says as much.

PREGNANT TREE

There is no need

to stand by the swell of your belly,

feel the kick,

listen to the echo

crying deep inside you.

Instead, I watch

a tiny sparrow

clinging to a branch.

The thin, swaying limb

is the safest place extant.

Yet the bird covets sky.

In one brave extravagant gesture,

it flexes it wings,

lets go that bough,

soars out of the tree’s

thick green uterus.

The sparrow flies and flies,

just to bless that moment

it gets airborne.

THIS SEASON’S DEAD

A formless night

in winter,

as ephemeral flakes fall

and sleep-bound fishermen

enlighten the waves

on tomorrow’s journey

in the presence

of decks rife with snow.

THE CICADAS

Seventeen years underground.

Seventeen years of such uncommon patience.

Then out they come for a summer, in our world,

sucking on sap of oak and willow,

laying eggs, vibrating their membranes,

shredding the air with their ticks, whines and buzzes.

Then seventeen more years underground.

As if deep in the dirt, stillness and silence, is the real life.

And the time up top is merely the dream,

the motor whir of a subconscious,

What we see is a cicada imagining itself as a cicada.

What we hear is the sound of an insect playing along.

————————————————————————————————————————

The Provider

(in Cascadia Mono font) – by koon woon

I. The Provider

Zap! The Provider did the dining table.

Ham & yams appear, so do cider and toast,

Three-flavored meat, garden-colored veggies,

and ice cream.

A bug falls in the attic –

CIA surveillance.

No matter. Mind your mind.

The Provider unfolds the newspaper.

There arise buildings and bridges.

In the advertisement section,

another client is sold a bill of goods.

Times like these the rain is incessant.

Twenty years ago, a house grazes on the hill,

short pines, daffodils,

statistically very sound.

A cold stream nearby holds small trout.

Water metaphors into banks and credit,

where cash is preferred over a lien.

Times like these the rain is incessant.

In the nearby sand a spider crawls onto

a sand castle. Windows are blank of meaning.

As the sun rays fall and splinter on driftwood,

undulant, undulant the tide rolls in.

Times like these the rain is incessant.

II. Dreamscape

Drip, drip the colorless liquid,

blood-red is the sea,

sun sunken into water,

children descend.

At times such as these the rain is incessant.

Let go of the rope,

the tiny hope of a sparrow’s chirp;

man’s gun finds war,

as water ebbs unregulated to sea.

At times such as these words are redundant.

The phantom moves beneath the sea,

darkness falls in Tangiers,

a man cracks a coconut,

this is how the brain is tapped.

At times the streets are empty,

Other times they exhibit clowns.

As the children sip sodas,

the sun drops at the edge of sea.

III. The Visit

“You should feel as good as possible,” said the psychiatrist. But each visit exceeds my assets.

Fire moving down the mountain as the identity matrix.

“We hear the student had a long grudge against the prof.”

More words lead to redundancy like cascading water

in a fountain in Spain.

Do not move against the river.

Do not descend if not having ascended.

At times like these the rain is incessant.

The man drops another dime in the meter

so as to induce the shrink to open his golden mouth.

The undertaker heaves a formaldehyde breath.

Incessantly the rain come down without mercy.

Times such as these words are redundant.

Times like these the rain is incessant.

I suppose this will go on even if unrecorded.

But see me again when I am hungry!.

IV. Death Merchants

“Notice, my child,” said Wang Po the woodcutter,

“how bugs war on the dung heap.

I am but a poor woodcutter, yet my axe

unnerve ancient trees.”

When in the wilderness, listen to the axe.

“A day’s labor merits only a bowl of gruel,

yet, I want to see your peasant dress

explode in the colors of October chrysanthemums.”

When granaries deplete to feed mounted archers,

and beggars go begging,

an arrow is shot at the imperial door,

Because in times like these the rain is incessant.

V. The Provider Again

Making his entrance,

man lets dog licks his scar behind the ear.

In making his exit,

man points the direction where standards fall.

In times such as this the one-song bird is king.

Sometimes it is unpopular to stop the rain.

(more to follow)

April 19, 2025, Koon Woon in Seattle

click here for old site of

Five willows literary reviewhttp://www.fivewillowsliteraryreview.com

The work presented at https://goldfishbooks.org/ has been meticulously edited by Koon Woon.

poem

“The Snow Man”

One must have a bottle of Gallo in this cold alley

And to shake the cops and other winos

And be on the look-out for some sucker to roll

It has been a long while since my abode

Was taken from me not because of ice or lice

But because of the drive for condos

That in this high rise reaching town

Where all the Californ Dreaming has lost ground

To the sound of broken bottles

Which is the brittle psyche of fife

Which leads the rats from places bare

To places that don’t any longer sustain life

For the dweller of the alley, who is on dope,

And nothing, I mean nothing, beats a quick fix,

Nothing that is pure nor is impure.

Koon Woon

2015

thank you for viewing!

five willows literary review

Leave a comment